Fighting a dragon or a snake is one of the basic motifs in cosmogonic world creation myths of many different cultures, while the interaction between the frog and the snake can be linked to fertility cult practices. Artefacts with identical depictions have been found in different parts of central Europe, hundreds of kilometres apart. They point to the existence of a previously unknown pagan cult that connected diverse populations of varying origins during the early Middle Ages.

“When the belt with the motif of a snake devouring a frog was discovered with the help of metal detectors at the site near Břeclav in southern Moravia, we thought it was a rare find with a unique decoration. However, we later found that other nearly identical artefacts were also unearthed in Germany, Hungary and Bohemia. I realised that we were looking at a previously unknown pagan cult that linked different regions of central Europe in the early Middle Ages, before the arrival of Christianity. That is why we organised an international research team to study the artefacts in detail,” says Jiří Macháček, head of the Department of Archaeology and Museology at the MU Faculty of Arts. The archaeological site previously made headlines for the discovery of an animal rib with an inscription in ancient Germanic runes. “The motif of a serpent or snake devouring its victim appears in Germanic, Avar and Slavic mythology. It was a universally comprehensible and important ideogram. Today, we can only speculate about its exact meaning, but in the early Middle Ages, it connected the diverse peoples living in Central Europe on a spiritual level,” adds Jiří Macháček.

According to archaeologists, the Lány artefact belongs to a group called Avar belt fittings, which were produced in Central Europe in the 7th and 8th centuries AD and were part of the costume of the Avars, originally a nomadic people who settled in the Carpathian Basin in what is now Hungary. Their fashion was often adopted by neighbouring peoples, such as the Slavs.

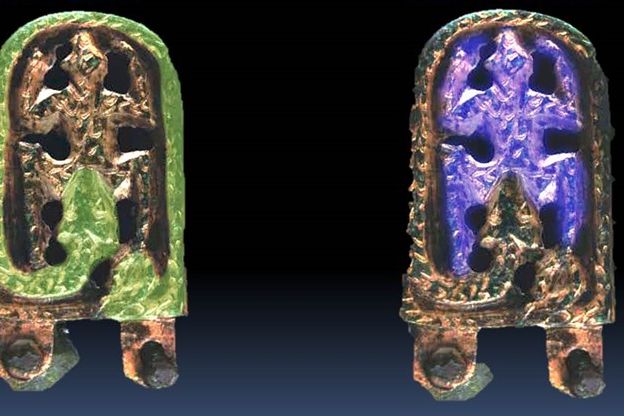

To analyse the Lány belt fittings and other similar artefacts, the researchers used state-of-the-art methods such as X-ray fluorescence analysis (EDXRF), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), a lead isotope analysis and 3D digital morphometry.

Stefan Eichert of the Natural History Museum in Vienna carried out a material and technological analysis which revealed that the majority of these bronze fittings were originally heavily gilded and produced using the lost-wax casting method. Ernst Pernicka of the University of Tübingen, using a chemical analysis of the lead isotopes contained in the bronze alloy, identified a common source of the copper from which all the discovered fittings were made – the copper used for the production of Avar bronzes was mined in the Slovak Ore Mountains. A morphometric analysis based on 3D digital models carried out by Vojtěch Nosek of Masaryk University also suggests that some of the fittings came from the same workshop or were derived from a common model.

Masaryk University archaeologists published their findings in the Journal of Archaeological Science, one of the world’s most prestigious archaeological journals. Their research at the site is funded by the EXPRO grant from the Czech Science Foundation.