Hamlet is one of Filip Krajník’s favourite plays because, as he puts it, it is “elegantly written and you can use it to show lots of things”. As a literary historian, he also teaches about Shakespeare in his course English Renaissance Theatre: Shakespeare and his Contemporaries. The impulse to take on the task of translating the famous tragedy came from the Prague theatre, as there was an interest in creating contemporary translations for a new generation of theatre goers. Hamlet in Krajník’s translation is now being performed at the South Bohemian Theatre in České Budějovice.

“Shakespeare has been translated into Czech since the end of the 18th century. And since then, as my much more accomplished colleague Pavel Drábek – who incidentally won the Rector’s Award fifteen years ago – says in one of his books, eight generations of translators have worked on him,” says Filip Krajník. “Each generation of translators, directors and audiences approaches Shakespeare differently, and the theatre evolves in the same way. If you went to see Shakespeare fifty or a hundred years ago, you would have seen a different performance than you would today. The translation should reflect that in some way. It is said that a play should be retranslated every twenty or thirty years, and the most recent translations of Hamlet by Josek and Hilský are both from 1999, so they will be a quarter of a century old this year. They are certainly not obsolete, but the time is quickly approaching when it would be good to have a new translation that competes with theirs and offers a different perspective,” adds Filip Krajník, who consulted theatre practitioners and scholars to make the translation easier to perform for actors and to preserve the gestural quality of the original.

A new translation can lead directors to new approaches more suitable for 21st century theatre. That is why the South Bohemian Theatre’s Hamlet, directed by Jakub Čermák, is an action hero who descends on a rope to Ophelia’s funeral. Krajník is pleased that, thanks to Čermák’s interpretation, his translation is helping to create a theatrical production that is attractive to young audiences. “The crazier the interpretation, the more honoured I am,” says Filip Krajník, who, although he prefers to read Shakespeare in print, is nevertheless interested in how his vision is represented by artists on stage.

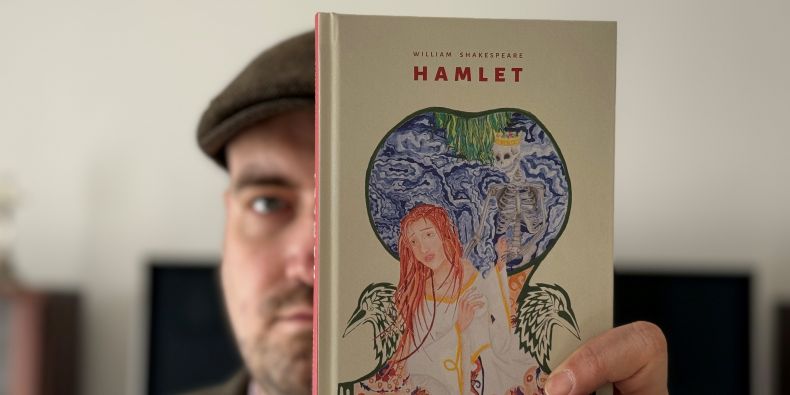

“I always try to translate a play with the complexity and intractability of the original and let the audience grapple with it, because Shakespeare’s original audience also struggled with the text. That is why I am always delighted when my translation results in a modern and innovative production,” says Filip Krajník. The book edition of his translation was published as part of a student book series, which Krajník plans to continue in collaboration with his doctoral student Anna Hrdinová, who serves as its editor. In addition to the play itself, the Hamlet publication includes an essay that provides the reader with context and introduces the structure and main themes of the play. “The footnotes provide additional context and illuminate problematic points in the play, such as allusions to other literary works or contemporary political situations and events that may be unfamiliar to today’s audiences.

The footnotes can also signal to potential directors that this part can be cut or changed,” Krajník explains. In the same vein, a student edition of Shakespeare’s contemporary Christopher Marlowe’s play Edward II was published at the end of last year, and a new Czech translation of Shakespeare’s comedies in one volume is also planned: Much Ado About Nothing and Double Falsehood, based on an episode of Don Quixote.

“Much Ado About Nothing will be translated by doctoral student Anna Hrdinová, and I am very pleased about this. Recently, the community of Shakespeare translators has begun to resemble a gentleman’s club, and there is a perception that a Shakespeare translator must be an older, charismatic university professor. Why don’t women translators flock to Shakespeare? It probably takes a certain amount of male vanity, the need to stand out, to do something different. I feel the same way. But women translators usually don’t and prefer to look for other plays to work on,” explains Filip Krajník in his introduction. He will also be translating the second Shakespeare play in the comedy volume, although the original has not survived. “We will be working with an adaptation of Shakespeare’s text. In the early 18th century there was a copy of Shakespeare’s play, originally called Cardenio, but it has not survived. This is why it is not always credited as Shakespeare’s play. His version of Don Quixote, which I will publish as Double Falsehood, has never been performed in Czechia and has never even been translated,” Krajník concludes.

And how did Filip Krajník approach “to be or not to be”, the most famous part of Hamlet? “In Czech, the literal translation of ‘to be or not to be’ has a much narrower potential for interpretation, but the verb ‘be’ can be understood not only in existential terms, but also in relation to the action taking place on the stage,” he explains. “My Hamlet is more action-oriented, so he doesn’t just reflect on life. The monologue makes it clear that he would like to do something. Should he commit suicide, attack King Claudius, or stage a play within a play? And that’s why, in my Czech translation, he says ‘Should I, or shouldn’t I’?”