Modern humans coming from Africa reached Europe approximately 45,000 years ago. However, Masaryk University researchers participated in a new genetic study published in the prestigious journal Nature, which showed that representatives of the Aurignacian culture – the ancestors of most Europeans today – arrived in Europe only about 38,000 years ago.

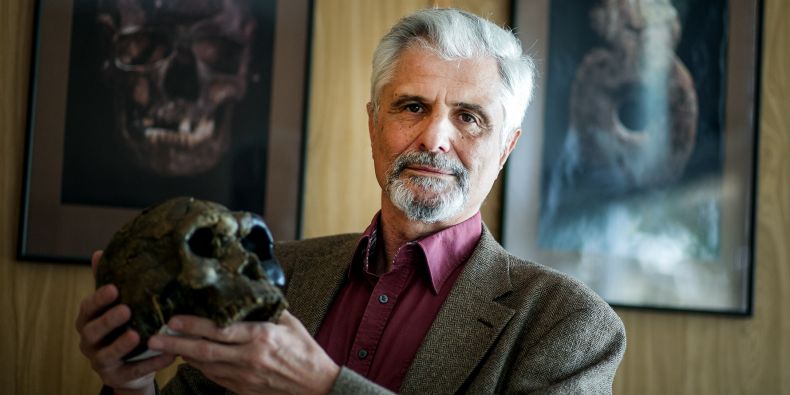

This shows that the genetic development of the European population during the Ice Age was far from straightforward. “It seems that the first anatomically modern humans did not arrive all at once, but that there were several waves of newcomers who settled in different regions of Europe, pushing the Neanderthals away,” says Jiří Svoboda, a co-author of the Nature study and the head of the Department of Anthropology at the MU Faculty of Science. “Stable populations developed 38,000 to 30,000 years ago and the culture which finally dominated among them was the Gravettian culture. The people who lived at the archaeological site of Dolní Věstonice were part of this culture.”

The “Věstonice genetic cluster”, as it was named by the researchers after the Czech archaeological site of Dolní Věstonice, prevailed in Europe for several thousand years. “There are findings from Italy, Austria, and Belgium that belong to the same group,” explains Prof. Svoboda, who also heads the Dolní Věstonice research base of the Institute of Archaeology at the Czech Academy of Sciences that provided the skeletal remains used for DNA analysis.

Even though the gene pool of the Dolní Věstonice “mammoth hunters” conquered Europe at one point and people belonging to this group developed a strong culture, it gradually disappeared and the relevant genetic groups only form about 10 to 15 percent of the current European population. According to Svoboda, more significant traces of genes of the people who lived in Dolní Věstonice during the Ice Age can currently be found, for example, among the Sami people who live mainly in Scandinavia.

The genome of the mammoth-hunting inhabitants of Dolní Věstonice prevailed until the glaciation peak of the last ice age, that is, about 25,000 to 20,000 years ago. Afterwards, representatives of other genetic groups began to spread in Europe and about 14,500 years ago, the genome begins to show traces of entirely new populations coming from the south-east.

The researchers analysed the genetic information of 51 individuals. One of them was a skeleton that was buried in Dolní Věstonice together with two other individuals and discovered in 1986. “We long resisted the applications for genetic analysis. It is a destructive method that requires drilling into the bones. We insisted that a meticulous morphological description be done before the analysis,” says Svoboda. The description was finally published in 2006.

In the meantime, the DNA examination method was improved, reducing the likelihood of sample contamination, which used to be a huge problem. “Touching the examined bone was enough to distort the results. In the earlier days of genetic analysis, researchers weren’t aware that modern DNA is very active and can penetrate deep into the discovered bones.

At present, our colleagues are able to distinguish between a modern genome and an old one with a certain degree of probability,” says Svoboda, explaining why they ultimately allowed a genetic analysis to be carried out.

Genetics goes hand in hand with archaeology

However, DNA is not the only indicator that is used by researchers mapping the development of European populations. “As palaeoanthropologists, my colleagues and I piece together the history of Europe during the Ice Age based on bones, artefacts, and technologies,” explains Svoboda. “Besides the samples needed for genetic research, we also provide geneticists with a framework for their research and the chronology of development.” He adds that the new genetic analyses do not, in principle, go against traditional palaeoanthropological findings. However, genetics is not the only science that brings new information.

The ongoing study of the sites at Dolní Věstonice and Pavlov has brought other interesting discoveries over the last several decades. Svoboda describes the research findings in the following way: “For example, we have long been thinking about the structure of the mammoth hunters’ settlements, as they were basically nomadic people. However, it turned out that three of the sites in Dolní Věstonice and Pavlov could have been inhabited year round, while other, smaller settlements served as seasonal bases for hunting and other purposes.” Experts have also been able to establish that these people ate not only meat, but also plants. Studies have found traces of starch, and according to the researchers, the hunters ground plant roots to make a simple type of flour. “They also knew how to fire clay. Moreover, some of the clay was found to bear prints of a regular grid-like structure, which means they also knew how to weave,” concludes Prof. Jiří Svoboda.